Extracts from http://dunkerley-tuson.co.uk , with the kind permission of Philip Dunkerley

Expansion of the cotton industry

In 1793, the year England went to war with

France. France might have been in the throes of a Political Revolution, but

England was experiencing the first years of its Industrial Revolution as the

cotton industry expanded rapidly to become England’s greatest, and sustained,

export earner. Along the River Darwen, south of Preston, from about 1784 several

water mills converted to drive carding and spinning machinery (based on

Arkwright’s water frame and Crompton’s mule)

Preston had been at a serious disadvantage with respect to most other Lancashire

cotton towns in that it neither had running water to power the new spinning

mills, nor was it situated on a coalfield. However there was plenty of coal in

Wigan, fifteen miles to the south, and some had been arriving at Preston from

the middle of the eighteenth century in flat-bottomed barges following

improvement of navigation on the River Douglas. Better transport was needed

though, and in 1792 work began on a canal from Wigan to Preston. By 1803 the

canal was in operation, complete with a substantial tunnel at Whittle le Woods.

A canal crossing of the Ribble Valley proved too expensive however so, instead,

a six-mile tramway was built from Walton Summit to carry the coal down into

Preston. Along this, horse-drawn trains of six wagons, each carrying two-ton

loads, passed on a double-track plate-way.

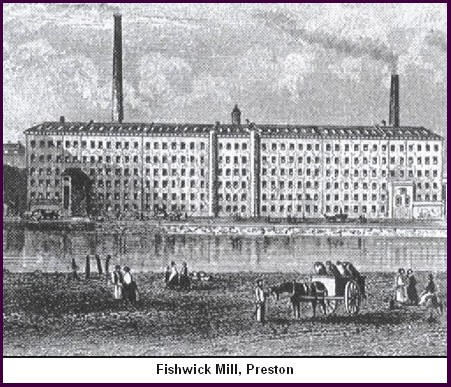

Preston was eventually to have over 40 mills, and

became one of the major centres for cotton manufacture. Its character as a

genteel market town was completely and irrevocably changed. Other cotton mills

were built south of the River Ribble, notably at Walton-le-Dale and Bamber

Bridge.

The new large spinning mills produced vast quantities of yarn and

presented the mill owners of Preston with the opportunity to create further

wealth by expanding the weaving industry of the area. Surprisingly, the

great advances in cotton spinning were not at first accompanied by any

significant mechanization of the weaving process. Power looms had been tried in

the 1780s, but it was not until about 1806 that a power loom capable of

practical application was developed, and even so, for various reasons, the power

loom was able to displace the handloom weaver only gradually. The annual

consumption of cotton in Britain in the 1780s was 14.8 million pounds, rising to

96.6 million in the 1810s, a more than six-fold increase at a time when

virtually all weaving was still being done by hand. Although machine weaving

began thereafter to increase rapidly, the number of handloom weavers continued

to rise to around 170,000 in the early 1820s before declining gradually to

perhaps 55,000 by the 1850s and to virtual extinction in the 1880s.

The

Workforce

The

Workforce

The burgeoning demand for handloom weavers from the 1790s was satisfied

from various sources. For one thing, the population of the country in general

rose persistently from about 1740, more rapidly from about 1785, and continued

to rise throughout the nineteenth century. For another, northwest England was

the locus of the highest rates of growth.

Several factors contributed to the increase in population, important among which

were earlier marriages and higher birth rates. Food prices had remained fairly

stable since the 1670s and there was a run of low food prices from 1730 to 1755.

It may have been this fall in the cost of living that permitted the earlier

marriages and therefore produced higher birth rates that set off the population

growth. Lower food prices also meant there was a little more money available for

other purchases, including better clothing, and so helped develop the domestic

market for cotton goods. In the rural area of Penwortham, Hutton and Longton it

would have been relatively easy to set up new looms and train up new cotton

weavers, based on the traditional skills that already existed there in linen

weaving. This pattern of working is very clear in the 1841 census data,

discussed below.

Some, however, of the rising rural population chose to migrate to the nearby

towns where there was a greater demand for labour and the prospect of higher

wages. Besides cotton-working there was much employment to be had in building

the new spinning mills and the rows of brick houses needed for the workers, and

in the associated trades that grew up to support cotton working – engineering,

transport and other services.

Besides the increase in population, other factors also contributed to the rising

industrial labour force. For example, the mechanisation of spinning made the

hand spinners, generally women and children, redundant, freeing some of them up

to work on the loom. In passing, however, we may note that there was still a

need for some women and children to work as ‘bobbin winders’, a tedious activity

essential to keep the weaver supplied with weft for his fly shuttle. Ben

Brierley, a notable Lancashire writer, was only one of innumerable young boys

who felt enslaved by this device, and often mentions how his father would hurl

empty bobbins at his head when he fell behind in replenishing them. One of the

terms of endearment used by his character Ab o’ th’ Yate to describe

his wife is ‘my owd bobbin winder’, and the expression ‘stopped for

bobbins’ was widely used in Lancashire to indicate a hold up in some job or

other.

A further source of new handloom weavers was the demobilised Lancashire soldiers

returning from the Napoleonic wars after 1815 who were desperate to find

employment. As evidenced in a parliamentary paper they commonly ‘exchanged

the musket for the shuttle’. Finally, from about 1800 the influx of Irish

workers, that was to turn to a flood by the time of the potato famine of the

1840s, had already begun.

The Preston area was as short of handloom weavers as many others in Lancashire.

Initially most of the weavers were ‘outworkers’, that is they worked on

traditional four-post looms at home or for a neighbour where they were provided

with yarn for warp and weft either direct from the spinning mills or via

middlemen, and wove lengths of cloth called ‘pieces’ for which they were paid. A

large number of the outworkers lived in the towns and were closely attached to

particular spinning mills that might provide housing. Rows of purpose-built

weavers’ houses, which included a special loom-room partly below ground level,

sprang up in Preston, often crammed as courts into the old medieval town

property boundaries. These houses were small and primitive and later came to

constitute fearful urban slums.

Other outworkers, however, lived outside the towns in rural or village locations

and were serviced from warehouses. Quite a few village communities expanded as a

result of this activity, such as Brindle, near Preston. Often existing houses or

farm buildings were adapted for weaving, but new cottages were also built

specially for the purpose. These might have had a loom-room either on the

ground-floor or as a semi-basement with windows at ground level to provide light

to weave by (see photo). The purpose-built cottages sometimes had space for

several looms, typically four, so that several members of the family, or

neighbours, could find useful employment, and they often had earth floors to

help maintain the high humidity that kept the cotton fibres soft and pliable.

The 1790s were boom times when the so-called modern idea of ‘working from home’

was actually widely achieved across Lancashire.

By 1816 the impact of the Horrocks mills on the villages was huge – they

employed 'a whole countryside of weavers, 7,000 in all' and other

local spinning firms must also have employed outwork handloom weavers. Thus the

scattered country weavers in villages such as Penwortham, Hutton and Longton

were integrated via putters-out into the weaving network, and indeed by 1791

John Horrocks himself had established a warehouse in Longton supplying weavers

with yarn and receiving the finished cloth. Joseph Livesey (born at

Walton-Le-Dale in 1794) was to say in his autobiography that ‘in the country

around Preston all the small farms in Walton, Penwortham and the adjoining

country places were ‘weaving farms’, having a ‘shop’ attached to hold a certain

number of looms'.

The Town Labourer

In the countryside, where village life still retained much of the

village structure, food might be grown and there was a family network that might

provide some support. However, even if only in passing, it should be noted that

the lot of the industrial worker who cut his links with the land deteriorated

badly from the late 1790s.

For one thing, labour in the spinning mills was often twelve or more

hours per day for five or six days a week. However, the Horrocks concerns

employed ten times as many weavers as spinners, and almost

from the start the conditions in which many of them were housed in Preston were,

to say the least, awful. Even as early as 1791 a writer told of the pull of

Preston on the inhabitants of the surrounding area, where they were tempted by

the prospect of ‘good wages at what they think easy work’ but then

found that they had to work in filthy, overcrowded conditions, paying high

prices for food and rents. In the autumn and winter they ended up on a poor diet

and were prone to ‘low and nervous fevers; in short, putrid and gaol

distempers, that often cut off men, leaving families behind’.

The years of the French Wars (1793-1815) were generally difficult for trade,

with wild fluctuations in food prices, availability of work, and declining piece

rates, and the following years saw the power loom continuously make inroads into

the ranks of the handloom weavers. In 1826 there were riots in which power looms

were smashed. There was a lengthy – but failed – strike in Preston in 1836, and

hunger stalked the town in 1841-2 at the time of the ‘Plug Riots’ when four men

were killed. It was not until 1844 that legislation restricted the daily total

of hours worked to twelve. Once the industrial worker lost his connection with

the land he had only his labour to fall back on and at times of poor markets

there certainly was awful hardship in many cases.