Housing

17thC

In Tudor times, Cornish labourers' cottages were tiny hovels with earth or "cob" walls and low-thatched roofs. Even the farmhouses had no wooden floors or glass windows, and their only chimney was a hole in the wall to let out the smoke. Beds in such houses consisted of straw and a blanket, and the only other furniture was usually a few pots and pans. The inhabitants' clothes were made of coarse homespun material, and in both winter and summer, they went about with their legs and feet quite bare. Older people had apparently grown so accustomed to this, that they could hardly bear to wear shoes, complaining that they made their feet to hot.

The food of the poor was equally coarse and scanty, consisting mainly of milk, cheese, curds, and black barley bread. Many scarcely knew the taste of meat, although fish was consumed in large quantities by those living near the coast. Sugar, potatoes, and most green vegetables were unknown in Elizabethan times, as were tea, coffee and cocoa. Richer people, of all ages, drank ale for breakfast and wine at other meals, but the poor usually had to make do with water, or sometimes whey. Although some farmers brewed their own beer, this tended to be very poor quality, and, as one 16thC traveller remarked: "it tasted as if pigs had been wallowing in it"!

19thC

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, conditions have changed little for the poor. Most cottages, especially in the mining districts, were built by the people themselves. The walls were usually made of cob, a mixture of clay and chopped straw, beaten hard; whilst the roofs were thatched. Stone was sometimes used, but only when it could be obtained free of cost.

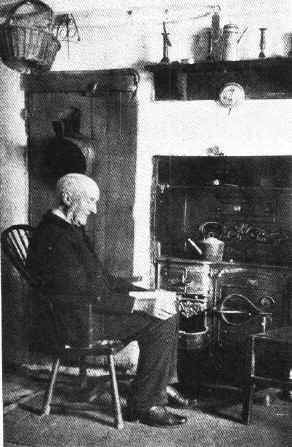

Such cottages were built anywhere where a bit of land could be obtained, often

in odd corners by the road-side, or on rocky lodges above the fishing coves. Hundreds more

were built by the miners amidst the shafts, burrows, and engine-houses of the mines which

gave them work. This photograph is of an old cottage at Gulval.

Such cottages were built anywhere where a bit of land could be obtained, often

in odd corners by the road-side, or on rocky lodges above the fishing coves. Hundreds more

were built by the miners amidst the shafts, burrows, and engine-houses of the mines which

gave them work. This photograph is of an old cottage at Gulval.

Life in these cottages was, of course, very primitive. Few had upstairs rooms, and where the family was large, a stage of boards, called a "talfat", was built beneath the rafters, extending over perhaps half the living-room, and reached by a ladder. The children would sleep here, lying close together to keep themselves warm on the bare, draughty floor.

Many cottages commonly had only one bedroom with a single bedstead made of crossed ropes, rather than springs, to carry the mattress. The latter was little better than a mat, about half an inch thick, packed with straw or chaff.

The two youngest children usually slept with their parents, with the baby in the mother's arms and the next youngest outside the father. Another mattress, placed on the floor beside the bed, sometimes accommodated as many as six children, and in winter, coats, dresses, petticoats, and even sacks would be used as bed coverings.

Downstairs, where the family lived by day, was equally cramped and wretched. The tiny window was often stuffed with rags, or had a slate inserted to take the place of a broken pain of glass. Wallpaper was an unheard-of luxury, and the insides of the rough walls were generally, though not always, whitewashed. The floor consisted of trodden-down earth, levelled occasionally with a shovel. Where stone was more plentiful, the flooring was often constructed out of great slabs of granite.

This single downstairs room had to serve for every purpose. It was the kitchen, nursery, wash-house and sitting-room combined. The furniture generally consisted of a long table, not much better than a rough carpenter's bench, with three or four hard, straight-backed chairs. In many cases, however, there was nothing to sit on but a form, which was placed along one wall, and a 3-legged stool, which stood in the chimney corner. The children simply sat on blocks of wood.

Hot-water systems were, of course, unknown, and the inhabitants had few opportunities to wash their bodies or their clothes. Even drinking-water often had to be fetched from long distances where there was no well near the house. At night, the cottages were lit by "rushlights", made from the pith of rushes dipped in tallow, and held in a clip attached to an upright iron stand. In Penwith, little earthenware lamps were often used, shaped like a heavy candlestick with one or two tiny wicks of rush or twisted cotton. They burnt an oil extracted from pilchards, which gave off a strong fishy smell.

|

In contrast to conditions in the poorer cottages, the houses of more substantial farmers were jolly enough places in which to live. In addition to the kitchen, back-kitchen, larder and dairy, most also possessed a parlour. This room was only used on special occasions, such as Christmas; on the mantlepiece might be seen a pair of china dogs, two or three brass candlesticks, and a little figure or portrait of John Wesley, or some other popular character. The most treasured piece of furniture of all was the "buffette", an old-fashioned corner-cupboard with a glass door. This contained the best china tea-set, and many nick-nacks and ornaments. The parlour was a show place, but it was the kitchen which was the real living of the house. Many of the old farm kitchens were very large, and in those days, the unmarried labourers generally "lived in" with the family, so that as many as 10 or 12 people could be sat down together at the long table at meal times. The kitchen ceiling was low, with dark oak beams. Against one wall there invariably stood a tall dresser with rows of shelves bearing cups, plates and dishes, often of pewter, which was made from local Cornish tin. |

Of all the fires that I do know

The furz and turf are best;

Give me an open chimney,

And you can have the rest.

Some people like the gas, I s'pose,

And some the 'lectric heat;

But me, I love the sunshine best

That's stored in stogs and peat.